A version of this presentation was given September 2, 2019 by ICOM Canada Board member, Michèle Rivet, C.M. at the 25th ICOM General Assembly in Kyoto, Japan. Michèle’s presentation was part of the “Decolonisation and Restitution: Moving towards a more holistic perspective and relational approach” panel (Session 1) moderated by Afşin Altayli (ICOM Secretariat) and Tonya Nelson (Chair, ICOM UK). The presentation spanned two rounds of talks.

From Decolonization to Indigenization: The Road to Equality

I would like to thank my ICOM Canada colleagues for their contributions, and to Marie Lalonde, Board chair, and the others attending here today.

ICOM’s potential contribution to the process of decolonizing museums and museology lies in formal and informal exchanges and collaborations between Canadian Members, within International Committees, and with ICOM members from countries that are, like Canada, in the process of decolonizing their museums.

In 2016, Indigenous peoples in Canada constituted over 1.6 million people, or 4.9 percent of the population, located mainly in Central and Western Canada. Canadian museums are in the process of moving from Decolonization towards Indigenization.

Decolonization restores the Indigenous worldview, culture, and traditional ways of life, replacing Western interpretations of history with Indigenous perspectives. Indigenization, on the other hand, recognizes the validity of Indigenous worldviews, knowledge and perspectives. It incorporates Indigenous ways of knowing and doing in museums, the best global example being between the Māori and the Pākehā peoples in New Zealand at the Te Papa Tongarewa Museum.

Canadians have for years established policies and practices on restitution and repatriation with museums, including the following significant events:

Following the 1988 Lubicon Cree boycott of “The Spirit Sings” exhibition during the Calgary Olympic Games, a working group was created with Assembly of First Nations members and the Canadian Museums Association. In 1992, the working group submitted a report titled Turning the Page: Forging New Partnerships between Museums and First Nations. It recommended increased participation of Aboriginal people in the interpretation of their culture and history, better access to museum collections for Aboriginal peoples, and the repatriation of sacred objects and human remains contained in museum collections.

Canada has also been involved in the development of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In November 2010, Canada issued a Statement of Support endorsing the Declaration’s principles. Since May 2016, Canada has been a full supporter of the declaration, without qualifications.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada released its report in 2015, calling the Residential Schools that affected more than 150,000 Aboriginal children “cultural genocide.” The Commission includes several Calls to Action involving museums, including Recommendation 67 that calls on

“the Federal Government to provide funding to the Canadian Museums Association to undertake, in collaboration with Aboriginal peoples, a national review of museum policies and best practices to determine the level of compliance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and to make recommendations”.

Following that recommendation, in 2018 the Canadian Museums Association initiated a Reconciliation Council of 14 Indigenous and non-Indigenous museum professionals from across Canada. This past June, the Canadian Museums Association appointed a Reconciliation Museologist.

Most recently, in April 2019, the Royal BC Museum and the Haida Gwaii Museum released the Indigenous Repatriation Handbook.

A Few Examples of Museum Initiatives:

Several trends towards indigenization, decolonization and reconciliation are becoming common among Canadian museums. Some select trends include:

- Programs directed at Indigenous Youth and prioritizing digital initiatives.

- Shared responsibility for permanent or temporary Indigenous exhibitions and education offerings planned by, or in collaboration with, Indigenous people.

- Including Indigenous perspectives in all exhibitions.

- Acknowledgement of traditional territories to precede all events, receptions, and guided tours.

- Standing advisory committees or councils to advise on every level of museum operations.

- Policies that include at least some Indigenous decision-making and/or representation on museum Boards of Directors.

- Inclusion of Indigenous worldviews through employment of permanent, full time Indigenous museum workers.

The Principles Underlying Museum Actions:

Decolonization rests on rebuilding relationships, establishing partnerships, and doing things “in a good way,” as many Elders say. The core principles are: Respect, Reciprocity, and Interconnectedness.

Respect:

Respect means honouring and respecting other living beings, giving full importance to tradition in the 21st Century. Examples of this can be found in:

Jonathan Hunt House, First Peoples’ Gallery, Royal BC Museum. The house is both a museum installation and a real, actual ceremonial house. (Image courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives)

Wearing our Identity, The First Peoples Collection permanent exhibition at the McCord Museum (Montreal), which includes works by contemporary Aboriginal artists who explore the notion of identity. Selected twice each year by an Aboriginal guest artist and curator, the works are integrated into the exhibition. (Image © Marilyn Aitken, McCord Museum)

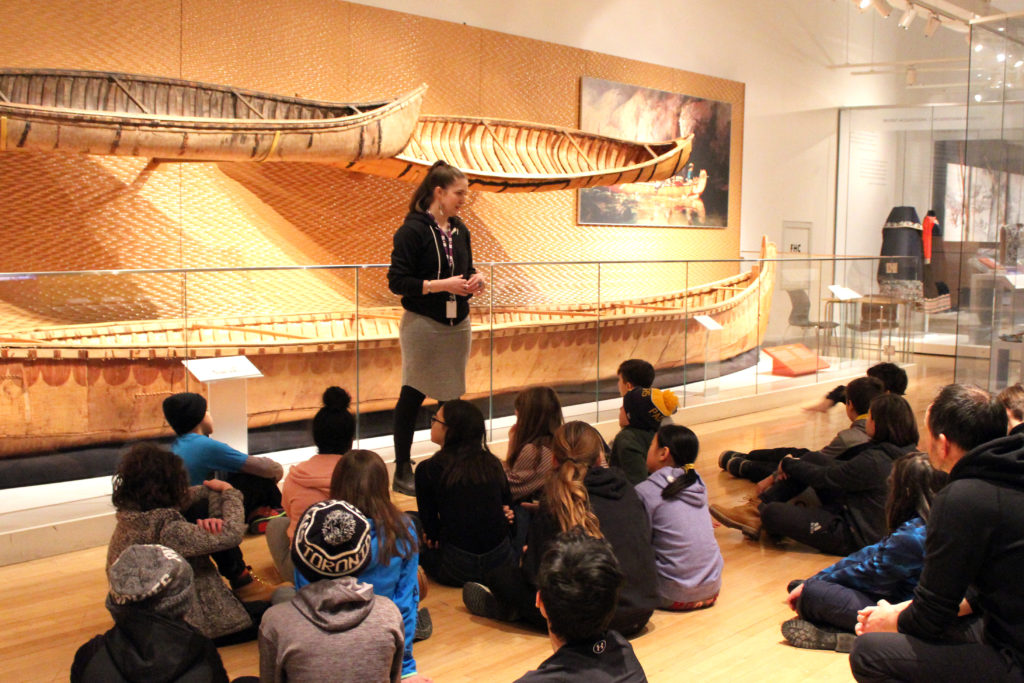

The Royal Ontario Museum’s Indigenous digital learning program Hack the ROM engages grades 4-10 Indigenous students and their peers throughout Northern and Southern Ontario. The multiple onsite and virtual visit program build students’ digital literacy skills to design and develop digital media projects such as games inspired by Indigenous ancestral objects in the ROM’s collection. (Image courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM)

Reciprocity:

Reciprocity is about the rights and obligations for people toward each other. For example, stewardship agreements between museums and Indigenous communities to ensure the care of artefacts through treaty negotiations, an important example being the Nisga’a Treaty of 2000. At the Canadian Museum of History, the 2017 opening of the Canadian History Hall marked the first time Indigenous and non-Indigenous histories were woven together in one expansive history of Canada.

On the right-side screen are four faces. In 2016 and 2017, the shishalh Nation (British Columbia) and the Canadian Museum of History collaborated on the development of this exhibition module for the Canadian History Hall showing shishalh ancestors. Two modules were constructed: one for CHH, the other for installation at Tems Swiya, the museum located on shishalh land. The images are facial reconstructions of 4,000-year-old ancestors based on ancestral remains. (Image courtesy of Canadian Museum of History, IMG2018-0032-0094-Dm)

The Challenges: Towards Indigenization

The third Decolonization principle, interconnectedness, leads us to challenges that museums are still facing today.

Interconnectedness:

Interconnectedness recognizes that rights of individuals and of the collective are intermeshed, that everything and everyone has purpose and that each is worthy of respect. Decolonization and Indigenization is about centring Indigenous ways of knowing and understanding the world and relationships, and making sure we respect those ways in all interactions with Indigenous peoples.

From the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, stories of Indigenous and human rights violations emphasize a shared responsibility for the past and for the present, to empower visitors to understand the past and to take action to change the future through the principles of interconnectedness. (Image courtesy of Aaron Cohen/Canadian Museum for Human Rights)

Indigenization means that museums are expected to achieve, according to Mariam Clavir, a Canadian conservationist emerita, a “’both/and’ model in bringing together First Nations and museum conservation perspectives on preservation.”[1] In other words, “museums have to become meeting places for ideas about the relationship of objects to history, historiography and the organization of knowledge in society.”[2]

Decolonization dismantles systems of thoughts that place the straight white person as standard,[3] it is an overhauling of the entire system. I suggest that indigenization is about hybridity and the “establishment of a culture of shared authority and power.”[4]

As we can imagine, there are still many challenges, including:

- Bureaucracies of large institutions sometimes complicating processes that are, from a relationship standpoint, much more about person-to-person interaction;

- Hiring and retaining Indigenous staff members; and

- Ongoing mistrust from some community members about museums appropriating their stories, their treasures, and their spirit.

To conclude, indigenization is about hybridity. It is much more than consultation, it is about sharing decision-making in full equality with First Nations, in every aspect of their life with the museum. Sharing decision-making is part of museums’ fiduciary duty to the society they serve. Canadian society is looking towards equality for all Canadians in this way. The road to equality…

Thank you.

[1] Clavir, M., (2002), Preserving What Is Valued: Museums, Conservation, and First Nations, UBC Press, 2002, 320 pages.

[2] Laforet, A., (1999), Concept of the object in the Nisga’a agreement and principle, Musée et Politique, (4e colloque de l’association internationale des Musées d’histoire).

[3] Kasmani, S., What does it mean to decolonize a museum, February 7, 2019, w., Museumnext.com.

[4] Phillips, R. B., (2011), Museum Pieces: Toward the Indigenization of Canadian Museums, Mc Gill-Queens University Press, 376 pages.